|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

© Commonwealth of Australia 2003 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted

under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any

process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth available

from the Department of Communications, Information Technology and the

Arts. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be

addressed to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Intellectual

Property Branch, Department of Communications, Information Technology and

the Arts, GPO Box 2154, Canberra ACT 2601 or posted at

http://www.dcita.gov.au/cca.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In the last decade Cambodia has achieved national reconciliation, peace and stability following many years of devastating conflict. However, the country remains one of the poorest in the world with social indicators that are amongst the worst in the region. Significant constraints on development are unchecked corruption and the weakness of public institutions, including the civil service and the judiciary. The lack of accountability of public institutions is also a disincentive to private sector investment and trade. The rural poor depend on subsistence agriculture and are particularly vulnerable to natural disasters and the continuing danger of landmines. Australia has a humanitarian and a practical interest in a stable and prosperous Cambodia which will contribute to regional economic growth and assist in combating transnational crime, including terrorism, people smuggling, narcotics and child sex tourism. Our partnership in development cooperation is important in fostering bilateral relations and progressing shared interests at all levels. The Australia–Cambodia Development Cooperation Strategy seeks to advance Australia’s national interest through contributing to poverty reduction and sustainable development in Cambodia.The strategic objectives of the program are to:

The three objectives are closely related and have equal priority. Reducing vulnerability is important to sustained increases in productivity and income, just as increased productivity reduces vulnerability. Strengthening the rule of law underpins the other objectives. The emphasis on governance and growth builds on AusAID’s approach during the 1990s, when the focus was on humanitarian assistance and reconstruction. This shift in emphasis reflects the increased opportunities to take a longer term, growth-focused approach in a more stable, peaceful Cambodia. It also takes account of the risks for Cambodia if it fails to become more integrated in the global economy and does not share the benefits of growth more widely. The new strategy sharpens the focus of Australian aid. The aim is for Australian aid to be targeted where it can make a difference. Assistance to health and education will be phased out. Other donors are providing considerable support to these important sectors; Australia can have a greater policy influence, and our limited aid resources will have more impact in other areas. Cambodia is very dependent on international aid; it comprises approximately one-third of the national budget. This increases the need for effective donor coordination and selectivity in our strategic interventions. It also emphasizes the importance of donor-government partnership approaches, including in policy dialogue. The Strategy sharpens our policy engagement and identifies key partnership mechanisms in Cambodia and in Australia. Growth in the agricultural sector will improve food security and the incomes of the rural poor and help stem the rural-urban drift. Our approach will build on past Australian success in improving productivity but will also assist with crop diversification and post-harvest value-adding processing. Effective extension and research services and good quality agricultural inputs are important, but the critical need to remove barriers to trade and investment in the sector is also recognised. By increasing agricultural efficiency and improving market operations, Australia will increase productivity and incomes of the rural poor. Australia will:

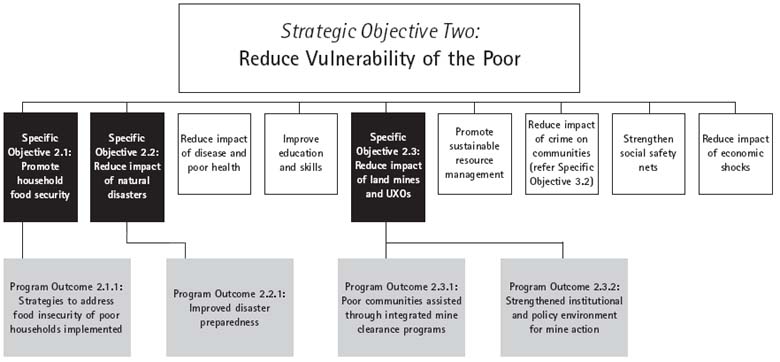

The poor of Cambodia are particularly vulnerable. Most live in rural areas where they are dependent on subsistence agriculture. They are often forced onto marginal flood-prone land, areas subject to drought or not yet cleared of landmines and unexploded ordnance. Food insecurity worsens the situation of many people. Social safety-nets remain weak with little government support. In seeking to reduce the vulnerability of the poor, Australia will:

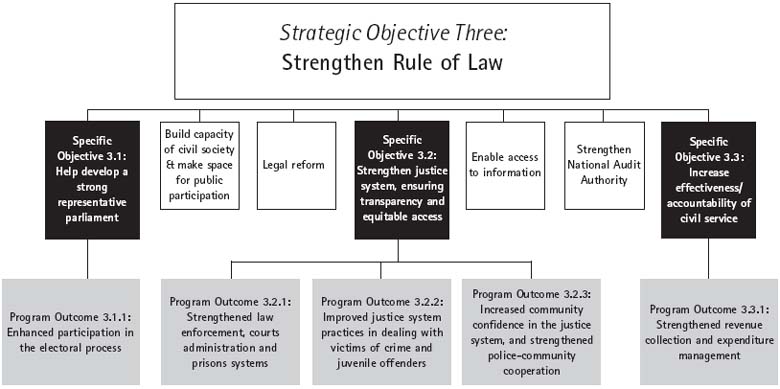

Sustainable growth and poverty reduction will not be achieved in Cambodia without improvements in governance. This is widely accepted and significant donor resources are dedicated to supporting Cambodia’s Governance Action Plan. Australia has identified niche areas where we are well placed to make a difference. Australia seeks to strengthen the rule of law through assisting the development of a strong representative parliamentary system, strengthening the justice system to ensure transparency and equitable access, and increasing the effectiveness and accountability of the civil service. Australia will:

1 AUSTRALIA'S NATIONAL INTEREST Promoting development, stability and prosperity in Cambodia is of both humanitarian and practical concern to Australia. Cambodia remains a very poor country, with significant humanitarian needs. A stable and more prosperous Cambodia will contribute to regional economic growth and assist in combating transnational crime, including terrorism, people smuggling, narcotics and child sex tourism. Australia supports Cambodia’s role in ASEAN and engagement with the World Trade Organisation (WTO), so that it can take maximum advantage of regional economic cooperation as well as global opportunities. Cambodia is a good friend of Australia’s in regional fora, and we rely on Cambodian support for Australia’s regional engagement. In the interests of greater stability, Australia promotes democratic development, governance reform, military reform, and accountability for the crimes of the Khmer Rouge period. Strengthening the rule of law is fundamental to each of Australia’s objectives in Cambodia, hence AusAID’s assistance in this area plays a central role in taking forward Australia’s whole of government interests. AusAID works closely with other Australian government departments and agencies active in areas relevant to strengthening the rule of law, including the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs, Attorney General’s Department, the Department of Defence and the Australian Federal Police. Because of the devastation and human loss inflicted by decades of conflict, Cambodia has a strong humanitarian claim for assistance in reconstructing institutions and infrastructure. The international community has a stake in preventing the recurrence of conflict in Cambodia, by promoting broad-based development. Australia has been an important partner in Cambodia’s reconstruction since the signing of the Paris Peace Accords in 1991. 2 CAMBODIA: DEVELOPMENT CHALLENGES AND RESPONSES Ten years after the United Nations supervised elections of May 1993 Cambodia is a very different country. After decades of conflict, the country is at peace and people are rebuilding their lives. There has been considerable infrastructure development, including rehabilitation of roads and construction of clinics and schools. The Government has stabilised the economy and maintained GDP growth rates averaging 5 per cent over the last decade. Cambodia is increasingly integrated into the world economy, with particular growth in the garment and tourism industries. A vibrant, though small-scale and largely urban, local private sector has developed. While agricultural productivity has grown more slowly, the country now produces an overall rice surplus (thanks in large part to Australian assistance), after many years of deficits. Cambodia is also making progress towards accession to the World Trade Organisation. A third national election will be held in July 2003. However, Cambodia remains one of the poorest countries in the world, with a per capita GDP of around US$300 – less than a dollar a day – and social indicators amongst the worst in Asia. Growth has been narrowly based in urban areas, particularly the capital Phnom Penh and tourist gateway Siem Reap. While urban incomes have risen, the majority of rural Cambodians remain desperately poor. Weak government institutions and high levels of corruption are serious constraints to development, with private sector growth particularly limited by an ineffectual judicial system. Government performance in service delivery and maintenance of infrastructure in rural areas is very weak, and there has been little improvement in social indicators over the last decade. Cambodia’s most disadvantaged groups include internally-displaced people, returned refugees, war widows, orphans, street children, squatters, ethnic minorities and people with disabilities. The prevalence of HIV/AIDS is alarming, with 2.8% of the population infected, although Cambodia has made significant progress in reducing the rate of spread of HIV.

Conflict and turmoil have contributed substantially to the problem of poverty in Cambodia today. This is highlighted by the fact that Cambodia and Thailand had about the same levels of GDP per capita in 1969 and in 2000 Thailand’s GDP per capita is over four times that of Cambodia (see figure 1). Cambodia started the 1990s with very low levels of human capital and physical infrastructure, and conflict and instability continued to be a problem through most of the decade. While the security situation is now substantially better, improvements in incomes and quality of life have been modest for the vast majority of Cambodians. The government lacks the capacity and resources to deliver services and maintain infrastructure in rural areas. Poor accountability for management of public resources allows considerable corruption and

wastage. The inadequate road network results in the isolation of many of the rural poor, particularly in the wet season. Only around a quarter of the rural population have access to safe drinking water, and less than 10 per cent have sanitation facilities. Education and health services, while improving, are poor in quality and inaccessible for many in remote rural areas. International NGOs working with local partners continue to be major players in basic service delivery, taking on roles government has so far been unable to fulfil. Opportunities for the poor to access services are also constrained by widespread rent seeking by government officials (who earn around US$30 a month). Teachers expect regular payments from their pupils, and many health workers charge for basic health care, because their salaries do not provide a living wage. Cambodia’s population is growing rapidly with the children of the baby boom of the 1980s now approaching prime reproductive and working age. The combination of high population growth with imbalances in the age-sex structure creates a planning challenge for the Cambodian Government. Food insecurity is a significant issue for the poor in Cambodia. Although Cambodia has produced modest rice surpluses since 1995, many Cambodians experience food insecurity due to lack of purchasing power, inadequate social safety nets, and poor transport and marketing systems. Current rice yield levels and cropping intensities are very low compared with those under similar ecosystems in many Southeast Asian countries. The poor are heavily dependent on natural resources as a source of livelihood but have insecure access rights and are vulnerable to the impact of environmental degradation. Ineffective natural resource management policies and corruption in resource allocation create significant problems for the poor and also impede private sector development. Access to land is a particular problem for the poor: although there is idle arable land, ownership is unequally distributed, and the poorest 40 per cent of households own just 12 per cent of the land. The poor are also vulnerable to losing their land through forced sale in a crisis (commonly due to a major illness in the family), or as a result of land appropriation by more powerful individuals. Cambodia’s farmers are highly vulnerable to climatic volatility. A large proportion of the population are dependent on rain-fed agriculture and live alongside rivers prone to seasonal flooding. Droughts and floods regularly affect large numbers of people; with the poor particularly affected as they tend to live in more marginal areas and have extremely limited capacity to cope with natural disasters. Almost half of all villages remain affected by land mines, a legacy of the years of war. Community bonds and social safety nets are weak as a result of the devastating social impact of the events of the Khmer Rouge period. Women provide a disproportionate share of agricultural and household labour, but have low status and limited access to education and health services. Women and girls are also particularly vulnerable to sexual exploitation and domestic violence. Addressing the causes of poverty in Cambodia requires sound analysis that targets key constraints. Governance issues create particular challenges. Cambodia’s status as a post-conflict country also influences development approaches. Public institutions, including the civil service and judiciary, are weak in capacity and suffer from corruption. Many civil servants and judges are poorly qualified for their jobs, and average civil service pay rates are well below a living wage. Jobs in the civil service, justice in criminal cases, and passing grades in school examinations frequently go to those who can pay. The civil service is highly politicised, and policy decisions can be frequently distorted by issues of politics, patronage, or self-interest. Unwillingness to delegate authority results in highly centralised control and very slow decision-making. Accountability of public institutions and public officials is very weak, and the problem is exacerbated by low remuneration levels for civil servants. Corruption reduces the revenue available to fund government services, distorts and weakens service delivery, and reduces incentives for private sector investment and trade. Weaknesses in the legal and judicial system are a major factor constraining foreign investment. There is very broad participation in the electoral process in Cambodia (in the 2002 Commune Elections, over 80% of all eligible voters cast a vote), and the conduct of elections has generally been technically sound. However, power remains highly concentrated, and there are significant concerns about election-related violence and intimidation. NGOs are active and vocal in political, human rights and development fields, although many remain institutionally weak. Civil society and the private sector generally play only limited roles in ensuring accountability of government. Women are poorly represented in decision-making roles in the civil service and in politics. A key governance concern is to promote transparent, equitable and sustainable management of Cambodia’s major natural resources, including land, forests, fisheries and water. There is an urgent need for enhanced involvement of stakeholders in natural resource management planning to ensure resources are utilised effectively for the longterm benefit of all Cambodians. Implementation of the legal and judicial reform and public administration reform agendas in Cambodia will be crucial to provide a framework for broad-based poverty reduction and growth. Governance constraints need to be factored into donor strategies and program designs. Addressing the challenges also requires attention to strengthening demand as well as the capacity for reform. The private sector is an important constituency for change; growth of small and medium enterprises is expected to lead to greater demand for a governance environment supportive of investment.While the Paris Peace Accords were signed in 1991, substantial areas of Cambodia remained affected by conflict until the late 1990s. Thus Cambodia’s development has been significantly constrained by conflict up until the last few years. Post-conflict countries have great needs for development investment but tend to have low levels of absorptive capacity, at least in the first few years of peace. While the needs are great, the institutional framework is weak and capacity to manage the development process is limited. In Cambodia, human capacity has been particularly damaged by decades of conflict and instability, and it will take many years to rebuild human and institutional resources. Physical constraints include lack of infrastructure in rural areas and the ongoing impact of landmines. In a post-conflict environment, long-term donor commitments to development and well-coordinated donor approaches are important. Sustainability of development programs is a longer-term goal; in the medium term donor finance for recurrent costs and ongoing technical support may be required. There is a need to give particular attention to rebuilding institutions that provide domestic order and security for citizens, raising public confidence in peace and reducing the risk of a resumption of conflict. Because of its post-conflict status, governance problems and low levels of economic and human development, Cambodia shares some of the characteristics of countries defined in development studies literature as ‘poor performers’ and ‘Low Income Countries Under Stress’ (LICUS). Lessons from the literature on promoting development in poor performers that may be relevant include:

Cambodia’s development strategies Following the 1998 elections, the Royal Government of Cambodia set out a strategic agenda for the next decade, known as the Triangle Strategy. The ‘Triangle’ comprises three sides:

Significant progress has been made in achieving the objectives of the first two sides of the Triangle. The third side, promoting economic and social development, is recognised as the most challenging objective. Cambodia’s National Poverty Reduction Strategy (NPRS) 2003-05, sets out the framework for poverty reduction, building on the Second Socio-Economic Development Plan 2001-05. The NPRS identifies eight priority poverty reduction actions:

The NPRS is built on a sound analysis of poverty and has considerable potential as a tool for better coordinating donor and government inputs. However, in its current form the strategy is essentially a comprehensive list of development objectives and activities, with little prioritisation. The risk of this strategy is that scarce government and donor resources will continue to be directed towards a wide range of objectives, resulting in relatively little overall progress. There has also been limited attention given to the need to schedule reforms effectively. The NPRS provides only limited direction to donors in setting priorities for assistance. There is a need for donors to continue to work with the Royal Government of Cambodia to develop realistic, well-targeted implementation plans for the NPRS, linked to the Medium Term Expenditure Framework. Cambodia’s Governance Action Plan (GAP) announced in 2000 outlines Royal Government of Cambodia’s strategic approach to addressing legal and judicial reform; fighting corruption; administrative reform and decentralisation; public finance reform; promoting gender equity; and strengthening natural resources management. The GAP established ambitious short to medium term targets, many of which have not been met. A ‘GAP-2’ is being finalised. The Royal Government of Cambodia places a high priority on WTO accession to maintain and enhance competitiveness, which provides an additional spur to address reform issues such as those in legal and judicial reform. Cambodia is receiving assistance to address constraints to integration into the international trading system under the Integrated Framework for Trade-Related Technical Assistance. The Government is taking steps to decentralise authority and responsibility for government service delivery. Decentralised governance was trialled in Cambodia through the Seila program. Seila (meaning ‘foundation stone’) was supported from 1996 by United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and other donors, and has been successful in channelling and managing investment funds in support of provincial and local level plans. Building on the Seila model, the 2002 Commune Elections established a new system of elected representatives at commune level. Financial and human resource constraints need to be addressed to ensure the Commune Councils can fulfil their role in ensuring service delivery is responsive to local needs. Cambodia’s development plans and strategies establish a sound framework for promoting growth and reducing poverty and inequality. However, there has been an inadequate setting of priorities and scheduling of resources to address key constraints. Progress in implementing many of the actions set out in these plans has been slow. The donor community and NGOs have been particularly critical of slow progress in legal and judicial reform and anti-corruption efforts of the Government. Capacity constraints are evident, but political will is also lacking. To address the challenges of the next decade and ensure continued foreign investment and donor support, more consistent reform progress will be crucial. Close to one third of Cambodia’s budget is funded by international aid. At the June 2002 Consultative Group (CG) meeting, US$635 million in Official Development Assistance was pledged by international donors. On average, since 1992, donors have disbursed around 75% of their total aid pledges. Of total disbursements between 1992 and 2001, 83% have been grants and the remainder concessional loans. Japan is by far the largest donor to Cambodia, followed by the EC, World Bank, ADB, and UN agencies. Important medium-sized donors include Australia, the US, France, the UK, Germany and Sweden. Donor support has helped to rebuild infrastructure, deliver services and develop capacity, but sustainability has been a problem. Aid has not always been well coordinated and has contributed to weak government ownership of the development process. Donors play a critical role in providing ideas and knowledge as well as resources to support governance reform and poverty reduction initiatives. To this end, donors are increasingly engaging in policy dialogue, sometimes linked to some level of program conditionality, in order to encourage more rapid governance reform. Annual CG meetings are an important mechanism for dialogue between the Royal Government of Cambodia and its partners on development policy and reform issues. Performance measures have been established jointly by donors and the Government for monitoring through the CG process. Progress on a number of these performance measures has been disappointing, even though they have been agreed by government and donors as realistic targets within the set timeframes. A number of key donors are working to improve coordination in policy dialogue, strategy development and program implementation, and Australia has played a significant role in these processes. The development of coordinated government-donor approaches is relatively advanced in the health and education sectors. Coordination has been less effective to date in other key areas including governance, agriculture, and small and medium enterprise development.3 AUSTRALIA’S AID PROGRAM IN CAMBODIA During the 1980s Australia provided substantial humanitarian assistance through NGOs and multilateral organisations. Australia announced the resumption of bilateral aid to Cambodia in April 1992. Over the last decade Australia’s assistance has shifted in focus from emergency assistance to longer-term development. The 1999-2001 country strategy aimed ‘to assist Cambodia make a transition towards sustainable, broad-based development’. Agriculture was identified as the major sector of focus, based on the importance of agriculture in promoting broad-based economic growth. The strategy also prioritised health, education and training, governance (particularly criminal justice) and de-mining. Australia has been a major player in the agriculture sector since the commencement in 1987 of AusAID assistance for a partnership between Australian scientists, the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) and Cambodia. IRRI support in re-establishing rice research and promoting improved technologies provided significant support for Cambodia’s move from a net food importer to producing overall rice surpluses. Net financial benefits to farmers as a result of Australian assistance are estimated at US$40 million per year. Australia has also provided significant assistance to develop agricultural extension capacity and is helping to address key constraints to commercial agricultural production and marketing. By the end of 2005 Australia will have spent approximately $41 million on mine action programs in Cambodia. This contribution has been instrumental in reducing the mine and unexploded ordnance casualty rates from over 3000 people per year to around 800. Australia has also been successful in improving awareness of the rule of law and human rights standards within Cambodia’s criminal justice system. Australian assistance has taken a practical approach, involving Cambodian counterparts closely in planning and implementation. Aid program support for key ministries in the criminal justice system has provided a sound basis for cooperation between the Cambodian and Australian authorities on a range of transnational crime issues. Support through Australian NGOs has complemented government to government assistance. NGOs have played very significant roles in rebuilding Cambodia, supporting the resettlement and reintegration of refugees, providing essential services to poor communities, helping particularly disadvantaged groups including street children and the disabled, and supporting skills development. Lessons learned from our experiences of development cooperation in Cambodia include the importance of recognising capacity and resource constraints and taking a long term perspective. Sustainability of donor interventions is a particular problem in Cambodia, due to low Government revenue, inadequate and unpredictable budget disbursement, meagre salary levels, and weak institutional capacity. To enhance project effectiveness and ensure commitment of counterparts, most donors, including Australia, fund salary supplements, performance incentives and recurrent funding. Such measures are, however, stop-gap approaches which can undermine sustainability. Working outside the public sector and encouraging direct cost recovery have therefore been important recent innovations in our agriculture sector program. A longer-term solution will also need to involve the implementation of comprehensive public administration and public expenditure reform, with coordinated support from donors. Australia’s aid to Cambodia combines bilateral, regional and humanitarian investments, support provided through Australian NGOs, and volunteer programs. Total Australian aid to Cambodia in 2003-04 is estimated to be $44.4 million. In addition to the bilateral program of A$24.5 million, Cambodia will receive an estimated A$19.9 million in other flows, including humanitarian assistance (mine action, food aid, refugee resettlement and reintegration, disaster preparedness, and emergency assistance), regional projects (e.g. anti-people trafficking, WTO related assistance, ASEAN Australia Development Cooperation Program), volunteer programs, NGO assistance, and support from other Australian Government agencies. 4 PROPOSED STRATEGY FRAMEWORK (2003 TO 2006) The goal for the Cambodia Australia Development Cooperation Program is: to advance Australia’s national interest through contributing to poverty reduction and sustainable development in Cambodia.The three strategic development objectives for the program are:

The three objectives are inter-related and mutually reinforcing; all are of equal priority. Reducing vulnerability is important to sustained increases in productivity and income, just as increased productivity reduces vulnerability. Strengthening the rule of law underpins the other objectives. AusAID will contribute towards these objectives through complementary policy efforts and program activities. The priorities under each strategic development objective have been identified taking account of the poverty analysis, the activities of other donors, and Australia’s capacity to make a difference. The objective tree (Attachment 1) sets out the specific objectives in support of the three strategic objectives for the program. This strategic approach represents a significant sharpening of focus compared to previous Cambodia country strategies. By targeting resources to a smaller number of areas where Australia can add value, we are seeking to increase our effectiveness and impact. The new strategy signals a move away from the health and education sectors, which were priorities under previous country strategies. Australia fully acknowledges the importance of investments in health and education in developing human capital and directly reducing poverty. The HIV crisis is also recognised as a major issue impacting on the poor. However, there are a number of major donors involved in these sectors, and Australia has been a relatively small player. Australia’s involvement in these sectors would have less impact than in other areas, and it is important that our limited aid resources are targeted in areas where Australia can make a difference. Agriculture, private sector development, disaster preparedness and governance are areas where Australia has the potential to play a leading donor role and support the development of more effective, coordinated government-donor approaches. To enable a sharpened focus on a narrower range of objectives, Australian support for sectoral health and education interventions will be phased out as current projects finish. Increase productivity and incomes of the rural poor Australia has a proven track record in the agriculture sector and can make a difference to the productivity and incomes of the rural poor. We have valuable expertise to offer, and there are relatively few other donors. Australia may be able to take a lead donor role to address the lack of a coordinated government-donor framework for agricultural investment which reduces the effectiveness of donors.Agriculture in Cambodia remains relatively inefficient; hence there is considerable potential for rapid growth in productivity and incomes from effective, well-coordinated investments. Growth in the agricultural sector will bring considerable benefits to the large proportion of the poor who are dependent on it, improving food security and incomes, and reducing the rate of rural-urban migration. Private sector growth can also be expected to be a driver for governance reform, given the importance of a transparent rules-based environment for investment. Australia’s contribution to increasing the productivity and incomes of the rural poor will build on our successes in the agriculture sector over the last 15 years. Australia will continue to assist Cambodia’s shift from a narrow focus on rice for food security towards a broader emphasis on development of rice and other products for trade. The program will support greater agricultural productivity, diversification, and value-adding. In particular, assistance will promote availability of effective extension and research services and good quality agricultural inputs, making appropriate use of government institutions and the private sector. To enhance our impact we will develop effective models for agricultural assistance that can be replicated by other donors. For example, we are already playing a leading role in efforts to develop standard approaches to supporting extension services. Close coordination with key donors will be an important element of our strategy. Integrated approaches will be explored, including assistance to address all of the barriers to growth of particular agricultural industries at each stage of the production and marketing process. NGO-led integrated rural development approaches will target specific poor districts. AusAID’s approaches will need to take account of the important role of women in agriculture and seek to ensure that programs are sensitive to gender issues. Land access issues will be taken into account in program development, and progressed through policy dialogue and monitoring/coordination of other donor efforts to promote effective implementation of the land law. Improving the efficient, equitable and sustainable use of water resources will be another important objective. Water policy considerations will be integrated into agricultural research and extension work and progressed on a regional basis through Australia’s support for the Mekong River Commission. Australia will also promote improved irrigation policies through strengthened government-donor coordination. Consideration will be given to how Australia can address other constraints to growth and investment in the agriculture sector, including in areas such as barriers to trade and foreign investment. Such issues will also be taken up in our policy dialogue with the Royal Government of Cambodia. The new Governance Facility will be used as a mechanism to provide flexible technical assistance in these areas. Support related to accession to the WTO will also be provided through regional programs. Options for supporting Cambodia’s decentralised rural development program (Seila) will be considered, where there are expected to be direct benefits for rural productivity. Reduce vulnerability of the poor Complementing activities in support of productivity, the aid program seeks to reduce vulnerability of the poor to household food insecurity, natural disasters and land mines. Australia can make a difference in these three areas. Although Cambodia has produced rice surpluses overall in recent years, food deficits are a problem at household level. As a result of Australian involvement in agriculture and our significant food aid contributions, we are well-placed to assist in promoting household food security. Floods, droughts and milder climatic volatility impact on agricultural productivity and can have a devastating impact on the poor who mostly only produce enough food for subsistence in a good year. We will help to strengthen disaster preparedness including through better coordination of government and donor efforts. Australia has made a long term commitment to assist Cambodia deal effectively with the scourge of land mines and unexploded ordnance (UXOs). Support will be provided for integrated programs of mine clearance, awareness and community development to help disadvantaged communities in mine-affected areas rebuild their lives. Australia will also work to strengthen the institutional and policy environment for mine action in Cambodia, promoting sustainability and more effective aid coordination. Innovative approaches to mine clearance, which take account of the reality that many mines and UXOs are cleared by villagers using unsafe practices, will be explored. Crime is an increasing problem for the poor and Australia is well-placed to assist, building on the success of AusAID’s work in the criminal justice sector since 1997. Support in this area is covered under Strategic Objective Three: Strengthening Rule of Law, but is also relevant as an issue of vulnerability. Activities to address vulnerability to crime will focus on ensuring the justice system responds to community needs, including in crime prevention. Strengthening rule of law provides an institutional foundation for development in Cambodia. Without improvements in governance, sustainable growth and poverty reduction cannot be achieved. Australia will contribute to broader government-donor efforts to build institutions and enhance predictability and accountability in application of the law. While a number of other donors are active in this field, niche areas have been identified where Australia has the expertise to assist and which would complement work under other objectives. Our assistance will be closely coordinated with the activities of other donors through the Governance Action Plan and other relevant Cambodian strategies. Identified priority areas for Australia include building free and fair electoral processes, strengthening the justice system, and improving revenue collection and expenditure management. Further work in refining these priorities will be undertaken during the first year of strategy implementation. Work on electoral processes will include enhancing civic and voter education programs and voter registration systems, with a particular focus on increasing the participation of women in the political process. Australia will also seek to promote an electoral environment free of violence and intimidation, through regular policy dialogue. Following the July 2003 election, we will consider what future assistance in this area may be appropriate. This may include a greater focus on working with civil society to promote democratic development. Support for the criminal justice system will take an integrated approach, working with police, courts and prisons to strengthen linkages with the community and build capacity. Australian assistance will promote transparency and equitable access to justice, and help build community confidence in the system. AusAID’s track record in criminal justice also enables the aid program to address the particular vulnerability of women and children to sexual exploitation and trafficking, which is an area of great concern to Australia. We will support efforts to combat people trafficking and child sex tourism through regional programs. Weaknesses in revenue collection and expenditure management are major constraints to accountability, capacity building and service delivery across the civil service. Targeting Australian expertise to address key issues in these areas would also help promote private sector development, contributing to Strategic Objective One. Progress will also be crucial in taking forward the Royal Government of Cambodia’s anti-corruption agenda. Support in this area is expected to be provided mainly under the new Governance Facility. The aid program will also contribute to building a stronger civil service through training for government officials provided through Australian Development Scholarships and the new Global Development Learning Network centre in Phnom Penh. Australia brings knowledge and ideas to the development process, not just finance. We seek to influence the policy of government and other donors to promote essential reforms. Cambodia now has a range of strategic plans based on sound analysis; the challenge for the next few years is to move from rhetoric to action, and to focus efforts in priority areas. Australia will promote coordinated government-donor action to implement key reforms. In Cambodia, Australia has particular influence on policy as a result of our neutrality and role as a key regional donor, as well as through our history of success and strong relationships in the agriculture and criminal justice sectors. We have good access to the Cambodian Government that allows us to successfully tackle complex and politically sensitive issues. We are also able to build partnerships between donors to achieve policy objectives. AusAID will engage the Royal Government of Cambodia across a range of issues, taking a leading role in areas where we are implementing projects, and supporting the policy positions of other key donors on a broader number of issues. For example, we anticipate taking a lead donor role in the proposed joint Government-Donor Working Group on agriculture. Australia will also increase engagement with the multilateral donors, and monitor their program outcomes where these are relevant to the country strategy. Through coordinating and leveraging the efforts of the major donors, we would aim to achieve a much greater impact than is possible through Australia’s relatively small aid budget. Areas of focus where Australia could play a leading role in developing policy positions and coordinating donors include: criminal justice (and transnational crime); developing an enabling environment for the private sector (including agricultural enterprises); and disaster preparedness. Other areas for policy engagement include: judicial reform, democracy and elections, public expenditure management, public administration reform, anti-corruption trade facilitation, land reform, irrigation, food aid and mine action. The new Governance Facility will provide a flexible mechanism for supporting policy dialogue with responsive technical assistance aimed at addressing governance constraints to economic growth. Support provided under the Facility will contribute to both Strategic Objectives One and Three. Priority areas for support will be considered by AusAID and the Royal Government of Cambodia on an annual basis, and will aim to complement other donor assistance. It is envisaged that initial priority areas would include:

During the next few years it will be crucial for Cambodia to overcome governance problems in order to attract foreign investment, maintain donor support, enhance private sector development, and ensure the rural poor benefit from growth. Australia will need to carefully consider appropriate responses, including strengthening incentives for reform and changes in focus or reductions in the aid program, should there not be steady progress in implementing key governance reforms. We will also need to look for opportunities to strengthen demand for reform. Our position would be closely coordinated with other donors and clearly communicated to the Royal Government of Cambodia. The Consultative Group meeting process will be a key forum for monitoring reform progress and presenting coordinated donor perspectives. Operational pipeline, implementation planning, and performance measures The approach to implementing the strategy will be set out in a program operational pipeline document. Program monitoring will be guided by a results frame. The program operational pipeline document will match new tasks with anticipated resource availability and set out the proposed sequencing of the new tasks required to successfully deliver the strategy. A number of major current activities are fully consistent with the new strategy, and most activities in areas that are inconsistent with the new strategy will be phased out by the end of 2003. The program is heavily committed during 2003-04, but funding will be available for major new activities commencing 2004-05. This will provide time for planning and design of new programs. An implementation plan will be developed and updated regularly, and will provide the basis for consultation between Australia and Cambodia on strategy implementation. The plan will note relevant ongoing activities (from bilateral, regional and humanitarian programs) and list required new activities and analytical work towards the achievement of each program outcome. The results frame will set out performance measures and means of verification for each program outcome. The results frame will be further developed and refined during the first year of strategy implementation, and revised as required during the strategy period. The importance of maintaining flexibility to respond to whole of government priorities in both countries and to new developments and changed circumstances is recognised. Steps are being taken to simplify delivery modes and introduce more flexibility to respond to emerging priorities. A new Governance Facility is being developed to meet needs for technical assistance addressing governance constraints to economic growth, with a particular focus on constraints to agricultural development. Contracts will be simplified and rolling annual plans used where appropriate to ensure programs respond to evolving conditions. The annual strategy review process, followed by bilateral High Level Consultations, should provide a forum for genuine program flexibility. The strategy objective tree and results frame will be modified as necessary through these review and consultation processes. Integrating Australian aid flows The new strategy framework provides a single framework for integrating bilateral, regional, humanitarian, multilateral and NGO aid flows. Humanitarian flows to Cambodia are particularly significant. Steps have already been taken to integrate longer-term humanitarian programs within the bilateral program framework, and these are reflected in the strategy objectives relating to vulnerability to food insecurity, disasters and land mines. Within this integrated strategy framework, efforts will be made to strengthen linkages between humanitarian and broader development activities in order to reinforce outcomes. For example, there are close links between agricultural activities and initiatives related to food insecurity and disasters. There are also excellent opportunities to align bilateral and regional program work in several areas. Regional program support for WTO accession and addressing sanitary and phytosanitary capacity building will complement bilateral work on improving the policy environment for agricultural markets. Regional support for the Mekong River Commission will make an important contribution to strengthening water policy and management, which will be vital in promoting agricultural productivity. We will also continue to promote effective links between bilateral assistance for criminal justice system strengthening and regional programs addressing the problems of people trafficking and child sexual exploitation. Cambodia is a substantial recipient of World Bank, Asian Development Bank and United Nations funds, and AusAID will work more closely with the Banks and UN system to ensure that their interventions are well-targeted, effectively monitored and closely coordinated with other donors’ efforts. The new National Poverty Reduction Strategy provides a valuable framework for more effective coordination of donor programs. Australia will also consider opportunities for co-financing and coordination with the Banks and UN agencies on specific activities. The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) has a major program of assistance to Cambodia which complements and reinforces bilateral program work in the agriculture sector. AusAID will look to strengthen collaboration with ACIAR over the strategy period. The new strategy will involve direct alignment of support for Australian NGO programs to the new program outcomes. Funding under two current NGO Australian ‘windows’, the Cambodia Community Development Program and the Mine Action Activity Funding, will continue until the end of 2004 and end of 2005 respectively. Future assistance through Australian NGOs will involve cooperation agreements linked to particular program outcomes. Further dialogue with NGOs will be conducted during the first two years of strategy implementation to confirm arrangements for these new partnerships. A new capacity building and accreditation program for Cambodian NGOs is proposed, which would complement support through Australian NGOs and the current small activities scheme. Such an accreditation mechanism could enhance NGO accountability and strengthen donor coherence in NGO funding. A review of Australian Development Scholarships (ADS) will be undertaken during the first year of strategy implementation in order to strengthen alignment between the ADS program and strategy objectives. The review will closely involve Royal Government of Cambodia partners. Integrating Information and Communication Technologies In August 2001, the Australian Foreign Minister, Alexander Downer, and World Bank President, James Wolfensohn, announced a joint initiative – the Virtual Colombo Plan. It aims to use the opportunities presented by information and communication technologies (ICTs) to enhance access to knowledge in developing countries. In Cambodia the program will explore innovative uses of ICTs for program delivery, including support for and use of the planned Global Development Learning Network centre in Phnom Penh. ICTs may be particularly valuable in capacity building to address constraints to growth and investment and in broad dissemination of agricultural research results. Uses for civic education will also be explored. The new Governance Facility will utilise ICTs as a delivery mechanism where appropriate. A risk management matrix for the country strategy will also be developed. Key risks include:

The risk management matrix will set out risk treatments for each major risk and will be reviewed and updated annually. Cambodian plans and strategies The aid program will support the implementation of the Royal Government of Cambodia’s Triangle Strategy through promoting economic and social development – the third side of the Triangle. Australia’s assistance for strengthening rule of law, reducing vulnerability and enhancing productivity will also make important contributions to the other two sides of the Triangle: building peace and security; and integration of Cambodia into the region and the international community. This country strategy is consistent with the objectives of the National Poverty Reduction Strategy, particularly the objectives relating to improving rural livelihoods, strengthening institutions and improving governance, and reducing vulnerability. Where appropriate, NPRS indicators will be used in AusAID’s performance monitoring framework. Making the NPRS work is an important objective for all donors. There is a need to target a smaller number of priority reform areas, with realistic schedules and budgets. Operational links between the NPRS, SEDP-II, GAP and other strategies also need to be clarified. AusAID will participate actively in efforts to strengthen implementation plans for the NPRS and other key strategies in areas relevant to Australia’s program objectives. At the June 2002 Consultative Group meeting the Royal Government of Cambodia proposed the formation of a Government-Donor Partnership Working Group under the CG mechanism to help build effective development partnerships with Cambodia’s external partners. This proposal was endorsed and the Working Group held its first meeting in October 2002. Australia was invited by the Royal Government of Cambodia to be a member of the Working Group, together with representatives of other interested donors. Initial areas of work for the Group include:

Australia’s approach emphasises the value of partnership arrangements in directing resources towards common visions, strategies and plans, rather than utilising common basket funding arrangements. We also recognise the importance of harmonising activities and procedures to reduce demands on partner governments. A pragmatic approach is needed which takes account of lessons learned and involves all partners in developing new strategies. Partnership involves accountability by all partners for performance and must be based on a foundation of trust. Australia already cooperates closely with other donors in a number of areas. For example, in agriculture our projects are coordinated with activities supported by IFAD, GTZ and the ADB, and are linked to the Seila decentralisation framework. In mine action and elections we have provided support through coordinated donor frameworks managed by UNDP. In taking forward this new strategy we will continue to work with key donor partners to achieve strategy objectives. Possible partnership areas and key donors/programs include:

Australia will be closely involved in the work of a select number Royal Government of Cambodia /donor working groups, linked to our strategy priorities. For example, we anticipate taking a lead donor role in the new agriculture working group, and being more active in the governance working group. On the other hand, we would reduce our involvement in or withdraw from working groups in thematic areas which are no longer strategic priorities for Australia. Involving the Australian community, key institutions, and Australian expertise The creation of new NGO cooperation agreements will be a key mechanism to involve the Australian community in strategy implementation. Possible areas for NGO partnerships could include: integrated approaches to agricultural development; promoting household food security; improving disaster preparedness; and mine action. Further consultations with the NGO community will be held to determine the focus and nature of these partnership arrangements. AusAID will also continue to engage with Australian NGOs on policy and implementation issues in specific fields, and will involve NGOs in strategy review processes. Cambodia has hosted a relatively large number of volunteers under the Australian Youth Ambassadors, Australian Volunteers International, and AESOP programs; a trend that is likely to continue. Opportunities to further involve volunteers in strategy implementation will be explored. Many placements are already in areas closely linked with strategy priorities. AusAID will continue to work closely with other Commonwealth government departments and agencies in designing and delivering assistance programs in areas of mutual interest. For example, we will continue to coordinate our activities in the criminal justice sector with related activities implemented by the Australian Federal Police, Department of Immigration Multicultural Affairs and Indigenous Affairs and Attorney General’s Department targeted at combating transnational crime. Further opportunities to involve universities,

agricultural research bodies, and state government agencies will also be

explored. The Governance Facility will provide a new mechanism for

building linkages between Australian and Cambodian organisations. Priority

areas for this strategy have been identified based on assessments of

Australia’s capacity to deliver appropriate expertise from government

institutions and/or the private sector. During implementation the

availability of relevant expertise in particular areas will need to be

kept under review.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Key areas for

policy engagement Improving policy, planning and monitoring of irrigation systems development and maintenance Implementing the land law for agricultural land Improving the policy environment for agricultural market |

|

|

Key areas for

policy engagement Improving effectiveness of food aid Implementing disaster preparedness Strengthening policy environment for mine action |

|

|

Key areas for

policy engagement Promoting an electoral environment free of violence and intimidation Promoting judicial reform Implementing public administration reform and public expenditure management reforms Implementing anti-corruption measures |

|||||||