|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

2. Development Cooperation in 2006 |

|

|

|

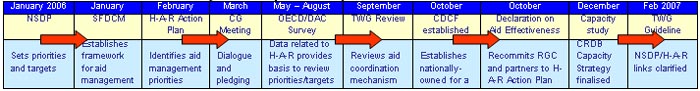

Development cooperation activities in 2006 This section reviews some of the key development partnership activities that took place in 2006 and associated efforts to enhance aid effectiveness. In January 2006 the NSDP was approved by Government following a series of consultations with development partners and civil society. The NSDP promotes effective national ownership and leadership of the development effort by providing a national, overarching framework for pursuing prioritised goals over the period 2006-2010. It is intended to guide resource allocations and to promote the integration of development assistance with national systems. It is therefore of strategic importance for development partners who are expected to align their country assistance strategies with these national priorities and systems. To ensure that aid management is fully consistent with the NSDP and with the Paris Declaration commitments of both Government and development partners, in February 2006 the Government approved its Updated Action Plan on Harmonisation, Alignment and Results. Priority activities were identified according to the five pillars of the Paris Declaration and responsibilities for implementation were agreed. Implementation arrangements for the H-A-R Action Plan were set out in the Strategic Framework for Development Cooperation Management (SFDCM), which was also approved in early 2006. The SFDCM provides an institutional framework for external resource mobilisation and aid coordination functions and outlines objectives and principles that guide the management of development cooperation. The Cambodian Rehabilitation and Development Board of the Council for the Development of Cambodia (CRDB/CDC) was mandated to be the Government focal point for resource mobilisation and aid coordination, providing support on-demand to all development partners and ministries/agencies on aid allocation and utilisation issues. Major Development Cooperation Activities 2006-2007 |

|

Development partners indicated their support for these arrangements in three important ways. First, a Multi-Donor Support Program (2006-2010) was established under CDC management and this Program has now been fully-funded by five partners. During the latter half of 2006 the Program supported the production of a Capacity Development Strategy that will inform the strengthening of Government's aid coordination focal point function over the next four years. Second, the Government and its development partners met at the Consultative Group (CG) in March 2006 to discuss the NSDP, the reform agenda and the associated need for more emphasis on strengthening aid management. After noting that the Government's ambitious reform agenda required further support and effort, the meeting concluded with a broad endorsement of progress made and a pledge of over USD 600 million from development partners. Finally, fourteen of Cambodia's major development partners signed a Declaration on Enhancing Aid Effectiveness in October 2006 and, although some donors insisted that it be non-binding, it usefully applies the global principles that both Government and its partners have endorsed to the context of Cambodia. The H-A-R Action Plan is implemented through the Government-Donor Coordination Committee (GDCC) that oversees the Technical Working Group (TWG) mechanism. With a view to improving the functioning of the TWG-GDCC mechanism, a review of both the CG and GDCC-TWG mechanisms was conducted by CRDB/CDC in its role as the Secretariat of GDCC. The CG mechanism review recommended strengthening partnership through enhanced Government ownership and leadership as a starting point. The review therefore proposed the establishment of the Cambodia Development Cooperation Forum (CDCF), a Government-chaired meeting with all national and international stakeholders with a focus on the NSDP and its associated financing framework. After a process of consultation on the CDCF proposal with development partners, and some amendments to accommodate their concerns, the proposal was submitted to Samdech Prime Minister on 28 September 2006 for approval.

The GDCC-TWG Review was also subject to an intensive round of negotiation and consolidation, a process that served to increase the quality and representative nature of the Review. The results of the Review were then used to prepare a 'Guideline on the Role and Functioning of the TWGs', which was endorsed by the Government on 23 February 2007. This paper attempts to clarify the role of the TWGs in supporting, and not substituting for, Government management of development assistance in the context of establishing or consolidating effective management of sector-wide programmes that are based on the NSDP. The highlights of the TWG-GDCC Review that were subsequently incorporated into the Guideline include:

The CG and GDCC-TWG Reviews also provided an opportunity to streamline the management of the Joint Monitoring Indicators (JMIs). This exercise has clarified the criteria for establishing indicators as well as improving arrangements for their management by the GDCC. It is intended that these Reviews, and in particular the new JMI arrangements, will promote a focus on achieving key results while also consolidating the mutual accountability characteristics of the development partnership. Based on these experiences, the Government has established some basic principles and a process for establishing the JMIs that reflect the spirit of mutual respect and accountability that is required to achieve Cambodia's development and reform goals. The basic principles that have been proposed are:

Trends in Development Cooperation This section considers trends in development cooperation by using data extracted from the CDC Database and data contained in the OECD/DAC Creditor Reporting System. It begins by looking more closely at the aggregate provision of development assistance, considering some of the principal features of development cooperation in Cambodia and the empirical nature of the aid coordination challenge in Cambodia. The analysis then turns to the NSDP and highlights the efforts that have been made to align development assistance to the NSDP, as well as some of the challenges that remain. Trends in disbursements are then considered, by both development partner and by sector, before a more detailed analysis is presented on four key sectors (agriculture, education, health, and infrastructure), highlighting how summary data on sector support can be quickly applied to facilitate evidence-based analysis and dialogue. The survey questionnaire that was used to collect data to facilitate this analysis is attached as Annex Three, a full description of the CDC Database, its structure and future development options is included as Annex Four and a reflection on the quality of data, and measures for its improvement over the medium-term, is attached as Annex Five. Additional data presentations are provided in Annex Six and the sector and sub-sector classifications, which are based on the NSDP priority sectors, are presented as Annex Seven. Long-Term Trends in Development Cooperation Over the period 1992 to 2006, a total of almost USD 7 billion was reported to have been disbursed by development partners to Cambodia (see Annex Six). These have included contributions of:

By far the largest single development cooperation contributor is Japan. Since 1992, Japan has provided 21% of all development cooperation resources. Other major contributors of grant aid over the 1992-2006 period are:

Cambodia: Concentration and Fragmentation in the Delivery of Aid The charts overleaf plot relative degrees of concentration and fragmentation in the provision of development assistance, first for a range of Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and neighbouring countries and then as a time series for Cambodia. This concentration is determined by the number of providers of development assistance in a country and the relative shares of their support in total development assistance1. The index shows that Cambodia is characteristic of a highly deconcentrated aid environment. Whereas a country with a higher index value may have one development partner, or an otherwise very limited number, providing a significant share of total aid, Cambodia has over thirty development partners which, with just a few exceptions, provide relatively equal shares of support. The

chart on the right, overleaf, shows that, as one might expect, the aid

environment has become markedly more 'competitive' over the past decade

as more partners have commenced or resumed the provision of support. It

is a little more surprising, however, that this trend has continued to

become more acute in the last 4-5 years, in part because of the entry of

new partners. |

|

Chart One. Concentration and Competition in the 'Market for Aid' |

|

|

Aid Concentration

(selected countries) 2005 |

Aid Concentration in

Cambodia 1993-2005 |

| Source: OECD/DAC Creditor Reporting System |

|

The empirical evidence suggests that the aid environment in Cambodia might therefore be described as one of the most competitive in the world. The OECD/DAC, in a 2004 'Survey on harmonisation and Alignment' in fourteen partner countries, found that, in such an environment, each partner, in an attempt not to be marginalised or to lose profile, is inclined to participate in every decision and to join every policy dialogue, resulting in a significant escalation in transactions costs for both development partners and government. Where this deconcentrated environment has led to increased competition between development partners, the effect can be that development partners, and the government ministry counterparts, become increasingly focused on the results of their own projects, losing sight of the broader and more strategic objectives of the national programme. The link between development assistance and results may be obscured, while resources committed by government to managing and brokering development assistance risks crowding out the growth of domestic accountability. This does not imply that direct measures need to be taken to 'increase concentration' in the delivery of aid. Rather, the position of the Government is that diversity must be preserved while working in partnership to address the symptoms of fragmentation. The Royal Government of Cambodia welcomes support from all of its partners and notes that, if carefully managed, this provides for innovation and a broad range of policy perspectives to inform the NSDP. Aid fragmentation across sectors and development partners A related concern for each aid receiving country is sector fragmentation, which refers not only to the extent to which multiple donors comprise the overall aid profile but also the degree to which the support of each development partner is dispersed across multiple sectors and projects. Calculating a Herfandahl Index for each sector – i.e. considering the number of partners in each sector and their relative sector shares - does indeed highlight that some sectors face a formidable coordination challenge. Although some 'sectors', such as governance, include multiple reform programs and a diverse set of activities across a reported 67 projects in 2006, it is clear that, for sectors such as health and education (with 109 and 79 projects respectively), there is a need to ensure that their sector programmes work effectively to lower transaction costs if the Government is to exercise effective leadership over the sector. It is also notable that the ministries responsible for agriculture and water, both of which are highly fragmented sectors (although also under-resourced as the alignment section, below, will highlight), together with the respective TWG, have recently finalised the preparation of their sector-wide programme, which comprises a strategic response to the aid management challenge in those sectors. Conversely, some sectors demonstrate a highly concentrated share of funding, often due to there being a single partner supporting that 'sector' (e.g. WFP, representing a range of delegating partners, providing food aid). The final set of analysis related to proliferation and fragmentation considers the profile of development partner support. This fragmentation, besides exacerbating the problem of escalating transaction costs in aid management, has been identified in the development literature as perhaps having an additional and more pernicious effect. This relates to the stripping of local capacity as each partner seeks to establish its own expertise in each sector in which it has a presence. The literature also highlights a tendency towards 'donor competition' that results in a focus on the achievement and attribution of project results as opposed to concentrating on the impact of the overall development effort in supporting the national programme2. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Source: CDC Database (derived). Higher index rating implies higher degree of sector concentration |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

By constructing an index for each development partner, weighted by size of disbursement and number of projects, as well as the number of sectors supported, it is possible to consider the degree of concentration in their support to Cambodia. In this case a composite index is constructed based on average size of project disbursement in 2005 and 2006 and a Herfandahl Index that takes account of the number of sectors and the amount of support associated with each development partner. Table Two, below, shows the variables that have been constructed. Making the assumption that average project size is a more significant indicator of fragmentation than the number of sectors that are supported, the Composite Index is based on a 70:30 weighting. Table Two. Composite Index of Project and Sector Fragmentation in Cambodia (2006)

Source: Data derived from CDC Database, April 2007 The Composite Index, based on this 70:30 weighting between average project size and sector concentration is presented in Chart Three, below. Chart Three. Composite Index of Project and Sector Fragmentation in Cambodia (2006)

This analysis therefore contributes to the effort to redress issues of deconcentration and fragmentation by filling the information gap that currently exists so that priority activities can then be fully and efficiently funded. This will include the identification of new approaches that, within the context of a sector strategy, promote operational efficiency within the sector, as well as allocative efficiency in aggregate resource allocation. The Government's response to this aid coordination challenge, therefore, is to:

Without improvements in aid efficiency, realising associated improvements in aid effectiveness may prove to be a challenging proposition. While this analysis on concentration and fragmentation can make a useful contribution to the aid effectiveness discussion, some of the analysis must be underwritten with a caveat. First, the usual note of caution must be observed regarding data quality; in this case some development partners have classified a significant amount of their support under the 'other' category, which distorts the overall profile of development support across all sectors. Second, many partners define a 'project' rather differently, aggregating or clustering a number of activities under a single programmatic heading while others may more narrowly define their activities and consequently be identified as having more projects. Excessive levels of deconcentration and fragmentation may impose additional transaction costs but it must also be emphasised that many partners, the UN in particular, have a mandated role in providing specialised packages of technical support across a broad range of priority activities. Similarly, the development banks, which are equipped as multilateral partners with significant expertise in many practice areas, often play the role of 'lender of the last resort' and so may therefore be expected to support a broad range of sectors. Finally, and most significantly, this analysis takes no account of the funding modality or of the mode of delivery, which may be through the non-Government sector or by acting as a silent partner in a co-financing arrangement. The harmonisation section in Chapter Three attempts to shed some light on emerging partnership arrangements and should be read in conjunction with this section so that policy prescriptions can be based on a more nuanced perspective on the delivery of development assistance. In conclusion, the requirement to maintain diversity when considering policy options underlines the importance of addressing deconcentration and fragmentation by establishing more coherent approaches to aid management and drawing on the objective competencies of each development partner. The promotion of some concept of donor comparative advantage has been increasingly discussed at a global level, including at the OECD/DAC, and, given Cambodia's dual characteristics of high levels of donor deconcentration combined with a highly fragmented approach to the financing of the NSDP, this approach may have some merit. It is important to add, however, that simply addressing the symptoms may not be sufficient. In addition to developing a more rational 'division of labour' it is perhaps more critical that more efficient programme-based approaches are developed that build national capacity to manage aid and to utilise Government systems. Alignment with NSDP Priorities This analysis considers the extent to which development assistance is aligned with relative NSDP priorities. As the NSDP is a five-year programme, and the delivery of development assistance is provided in discrete annual disbursements, much of the analysis uses profiles - or percentage shares – to gauge the extent to which disbursements are consistent with NSDP priorities (detailed in Table Three, below). Given that annual funding levels in 2005 and 2006 were broadly in line with the NSDP's implicit annual targets, an analysis that is based on distributional profiles is an acceptable methodology by which to consider alignment issues. This approach allows the annual flow of aid to be compared to the Government's desired profile of ODA over the medium-term, thereby allowing for alignment of Government priorities and development partner financing to be compared. Table Three. NSDP Allocations (2006-2010)

Source: NSDP Table 5.2 The departure point is to consider the extent to which the funding that was indicated as committed for 2006 to Government during the preparation of the Public Investment Programme (PIP) is aligned with NSDP priorities. The chart below shows a strong correlation between the NSDP financing profile and the shares of development assistance indicated in the PIP, demonstrating that, at least at the level of commitments, there is a very close alignment of aid to national priorities. This relationship is confirmed statistically as the slope of the line (which represents the statistically best fit) is close to 1 (indicating a unitary relationship between the NSDP and PIP commitments) and the 'closeness of fit' to the line, with the exceptions of transportation, rural development and governance (relatively over-funded), and education and health (relatively under-funded), is statistically quite strong. The next piece of analysis considers the extent to which the 2006 funding that was indicated as committed to line ministries during the preparation of the PIP is translated into disbursements. Overall, the PIP was a good aggregate predictor of resource availability as 2006 commitments are estimated at USD 599.2 million against a provisional estimate of actual disbursements of USD 594.8 million. The charts below show that:

From this analysis it is clear that: (i) there needs to be more attention paid to the resource commitment and budgeting exercise for external funds; and (ii) that the translation of commitments into disbursements needs to be more closely monitored at sector level if funding for NSDP priority activities is to be assured. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| Content | Back | Top | Next | |

|

Home | 1st CDCF Meeting | 8th CG Meeting | Partnership and Harmonization TWG | GDCC | Policy Documents Guidelines | Donor Dev. Coop. Pgm. | NGO |